Considered an American literary classic, To Kill a Mockingbird is Harper Lee’s only book. Of course, she and Truman Capote grew up together in Monroeville and remained friends and cooperative writers for life. Her book was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1961. It has been translated into some forty languages and has sold well over 30 million copies to date worldwide. Nelle (as her friends and family call her) Harper Lee was presented the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2007 for her contributions to literature. Finally, librarians across the country have named To Kill a Mockingbird the best novel of the twentieth century!

Here is a hand-written letter from Ms. Lee declining an invitation to attend our “Big Read” due to her present health situation.

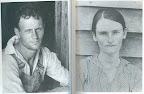

In 1936, writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans, both working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), visited Hale County, Alabama, where they zeroed in on three poor white sharecropper families as subjects for a magazine article. They recorded their daily lives and struggle for survival in the aftermath of the Great Depression and the onslaught of the New Deal era. The resulting book with accompanying photographs, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), eventually established the reputations of Agee and Evans, but did nothing to improve the plight of the three Alabama families. Three of Walker Evans’ most famous photographs from the book included three members of the Gudger family, George and Annie Mae and their ten year-old daughter, Maggie Louise. Changed for the book to protect their actual identities, their names were really Floyd, Allie Mae, and Lucile Burroughs.

Here are Walker Evans’ images of the Burroughs and here are their graves today in Oak Hill Cemetery in Moundville, Alabama. Later in life, Lucile, who always wanted to be a teacher or a nurse, killed herself by drinking rat poison. (Credit: Walker Evans from Let Us Now Praise Famous Men by James Agee and Walker Evans. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1941; modern images by Terry Barkley.)

The three sharecropper families lived up this dirt road on Hobe’s Hill (actually Mills Hill) between Moundville and Havana.

Let Us Now Praise Famous Men has also become something of an American classic and is taught in colleges and universities nationwide. When I was a graduate student at Harvard University, I learned that the book was required reading for freshmen students in Harvard College.

This book has also done much to stereotype Alabama and her people in the eyes of the rest of the nation and the world, and it has been roundly criticized and/or praised ever since its publication in 1941.

Fifty years after the publication of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the writer/photographer team of Dale Maharidge and Michael Williamson returned to Hale County to document the remaining original members and their descendents from the three sharecropper families. They discovered that little had changed for the families despite the fame of Famous Men. Their ground-breaking book, And Their Children After Them, a masterpiece of research, writing and photography, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction in 1990.

By the way, the sites of the three sharecropper farms are just north of the village of Havana in Hale County, while the site of Henry and Julia Tutwiler’s Green Springs School is just southwest of Havana.